Research shows that 90% of diets fail, with most re-gaining the weight (and even more!) over a 5 year period. While there are lots of variable reasons why diets fail, one of the most important issues is constant hunger. Of course, when it comes to fat loss, one of the most basic principles is being in an energy deficit – eating less total food or calories than you burn per day. This is where the well-known recommendation: “eat less and move more” came from.

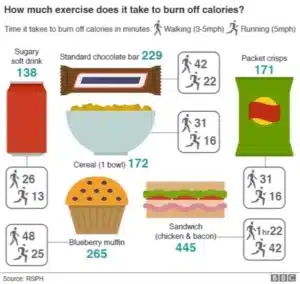

Just look at this image below, demonstrating the amount of time needed to burn off common foods.

As you can see, it requires a TON of activity to burn off some of your favorite foods. The standard approach is likely to fail, as it’s very easy to eat 500 calories but very hard to burn off 500. Therefore, if you want to create a calorie deficit, you are going to have to modify your diet and implement new strategies to lose weight. Read on to learn how to lose weight without counting calories.

Source: http://www.bbc.com/news/health-35322168

Here are 5 of the best strategies to reduce hunger and lose fat, without the need to count calories or track all your food.

1. Eat Slowly

Remember that time you came home from work ravenous, took out a bag of your favorite chips and proceeded to finish off the entire family-size bag before you even noticed it?

Eating like this can actually override your body’s satiety signals — such as the fullness-promoting hormone, leptin and glucose-like peptide 1 and neuropeptide y —that tell your brain it’s time to stop eating (1, 2). Usually, you don’t even notice the hundreds or thousands of calories you just consumed in a matter of minutes.

Researchers have found that slowing down your eating speed may, in fact, work to reduce your food intake. A study published in Psychosomatic Medicine found that when subjects were instructed to eat at a fast speed they consumed more total calories (2).

Other studies have found similar results, but in the opposite manner. Slowing down their meal eating time resulted in a decrease in overall food and calorie intake (3, 4, 5, 6)

In particular, one study exemplifies the power of how fast you eat on the total amount of calories you consume (7).

A mix of overweight and individuals of a healthy weight went through both a fast and a slow-eating protocol. During the slow phase, they were prompted to chew each bite thoroughly and set their utensil down between bites. The fast protocol involved researchers telling subjects to eat “as if they were on a time constraint” and to “take as big a bite as possible.”

On average, the fast eaters consumed their meal in nine minutes, whereas the slow eaters consumed their meal in 21 minutes. The fast eaters consumed an average of 102 calories per minute, versus 39 calories per minute for the slow eaters.

Over the course of the meal, the fast eaters consumed 99 more calories than the slow eaters did.

2. Eat More Protein, Especially at Breakfast

Whether you’re an avid weight trainer, runner, athlete or just casual gym goer, protein will help you take your performance and physique to the next level.

When it comes to weight loss, protein is one of the most powerful tools because it not only helps to keep you full (8, 9), but also can help you to burn more calories throughout the day (10, 11, 12).

Studies have shown that eating more protein will naturally help you to eat less food; one study suggested a huge 30% less (13). Best of all, it has been shown that even when people are allowed to eat as much as they want, having a higher protein intake results in weight loss (14, 15, 16).

Even more intriguing, there is research that one of the most important times of the day to get in a good amount of protein is at breakfast (17,18,19,20).

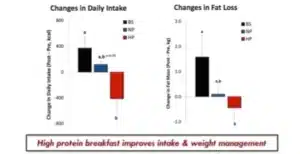

Most recently, a high protein breakfast was shown to result in prevention of fat gain, naturally lowering daily total calorie intake, and reducing daily hunger (17). As shown below, those represented by the black bar consumed a high protein meal and lost more fat and had a noticeable decrease in calorie/energy intake.

Source: Leidy, H. J., Hoertel, H. A., Douglas, S. M., Higgins, K. A., & Shafer, R. S. (2015). A high‐protein breakfast prevents body fat gain, through reductions in daily intake and hunger, in “Breakfast skipping” adolescents. Obesity, 23(9), 1761-1764.

An easy way to get more protein into your diet is to have a high quality source- eggs, meat, dairy or use a supplement such as Whey Protein etc. at every meal.

{{cta(‘8c7c8cff-00e5-4cb0-844a-5352a5b5029f’,’justifycenter’)}}

3. Optimize Your Fluid Intake

Your body’s signal for thirst is not very powerful; combined with a busy lifestyle it’s very easy to be chronically dehydrated.

By the time you feel thirsty, it’s possible that you are experiencing some of the consequences associated with dehydration such as irritability, fatigue, lack of focus, and decreased exercise performance (21, 22)

When we are dehydrated, our body will actually increase hunger as food also contains water (23, 24, 25). As a result, we experience a strong urge to eat, even if we just ate an hour ago.

In addition, even if you are not hydrated, drinking water before or with a meal can help you to eat less and, as discussed, help you lose weight over the long term (26, 27, 28, 29, 30).

In a study published in Nutrition Review, researchers found that substituting water for other beverages can help you to consume fewer calories at mealtime (29). Replacing water with sugar-sweetened beverages was found to increase energy intake by 7.8%, and replacing it with juice or milk was found to increase intake by 15%. In contrast, consuming an artificially sweetened, calorie free beverage actually reduced energy intake by a small 1.4% (29).

Another study found that simply including 500mL of water before meals over a 12 week period resulted in a 44% greater decline in weight over the 12 weeks than the non-water group (30). Both groups received individualized instruction by a registered dietitian on a hypocaloric diet (women: 1,200 kcal, men: 1,500 kcal), with the only difference being one group including 500mL of water before each meal (30)

As you can see, fluid intake is extremely important for several reasons. If you consume too little water you are more likely to over-eat. In contrast, if you consume additional water, especially around meals, it can help you eat fewer calories. Finally, by switching sugary drinks for calorie free alternatives and water you can quickly reduce calorie intake and lose weight.

4. Eat Higher Volume Foods

Did you know that your stomach is actually a “volume counter” instead of a “calorie counter”?

Your body’s reaction is far more responsive to the total volume (e.g. portion size / grams) of food than it is to the actual amount of energy in that food (31,32). Taste aside, that’s why it’s easier to work your way through half a box of cereal with ease, but struggle to finish a plate of broccoli.

Think about it logically: your stomach doesn’t realize the amount of energy in food for several hours later, once it’s been fully digested and metabolized. By this time, you have finished the meal and may be coming onto the next. However, at the time of eating your body is very sensitive to the volume or size of food – imagine it being like a shopping bag, it will only tell your brain to stop eating, once it becomes full of groceries!

For a great strategy try swapping out more calorie-dense foods such as sweets, fried food, breads, some grains, and even “healthier” choices such as dried fruits or fruit juice, in exchange for low energy dense foods such as leafy green vegetables, berries, and other more filing foods.

These foods have a low calorie density, meaning that they contain a small amount of calories for a large amount of food. The difference can be huge when it comes to weight loss. Consuming low energy dense foods has been repeatedly shown to result in greater weight loss than when you eat higher density foods (33, 34, 35, 36)

In addition, higher volume foods tend to be higher in fiber, vitamins, and minerals. Fiber is also great at slowing the digestion of food, reducing cravings, and promoting fullness. Combined, this is a top strategy for losing weight without hunger or counting calories (37,38,39).

Here’s a list of low-calorie foods and food groups:

- Unprocessed meats and fish,

- All salads and vegetables,

- Beans and Legumes,

- Natural, sugar free, yogurt,

- Most fruits but in particular berries.

5. Improve Sleep and Rest More

Poor quality and reduced sleep is linked to obesity and chronic diseases (40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45) In fact, short or disrupted sleep has been shown to increase the risk of obesity by 89% in children and 55% in adults (45).

You may have noticed before that on days after a night of short sleep, you tend to have more cravings and eat more. This is because a poor night’s sleep can disrupt hunger-regulating hormones like ghrelin and leptin which result in you eating more food throughout the day (46, 47, 48, 49, 50).

Additionally, when you don’t get enough sleep, it can cause your body to increase the amount of the stress hormone cortisol, which can play a large role in accumulating more body fat and increase the risk of common chronic, western diseases (51,52,53).

Improving both the quantity and quality of your sleep habits can play a profound effect on fat loss, sports performance, food intake and most importantly, overall health and disease risk.

Conclusion

For most people, counting calories is just an obsessive habit that they would sooner avoid. Diet, exercise and fat loss is complex enough, without having to weigh out every piece of food that goes into your mouth.

However, by following these simple strategies you can immediately cut calories and start losing weight:

- Slow down your eating speed

- Eat 30-40 grams of protein at each meal

- Drink water throughout the day

- Replace high calorie-dense foods with lower calorie foods.

- Get 30 minutes more sleep per night

Apply them today for long-term success without the need to count calories.

References

- De Silva, A., & Bloom, S. R. (2012). Gut hormones and appetite control: a focus on PYY and GLP-1 as therapeutic targets in obesity. Gut Liver, 6(1), 10-20.

- Kaplan, D. L. (1980). Eating style of obese and non-obese males.Psychosomatic medicine, 42(6), 529-538.

- Shah, M., Copeland, J., Dart, L., Adams-Huet, B., James, A., & Rhea, D. (2014). Slower eating speed lowers energy intake in normal-weight but not overweight/obese subjects. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics,114(3), 393-402.

- Scisco, J. L., Muth, E. R., Dong, Y., & Hoover, A. W. (2011). Slowing bite-rate reduces energy intake: an application of the bite counter device. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 111(8), 1231-1235.

- Andrade, A. M., Kresge, D. L., Teixeira, P. J., Baptista, F., & Melanson, K. J. (2012). Does eating slowly influence appetite and energy intake when water intake is controlled? International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 9(1), 1.

- Robinson, E., Almiron-Roig, E., Rutters, F., de Graaf, C., Forde, C. G., Smith, C. T., … & Jebb, S. A. (2014). A systematic review and meta-analysis examining the effect of eating rate on energy intake and hunger. The American journal of clinical nutrition, ajcn-081745.

- Smit, H. J., Kemsley, E. K., Tapp, H. S., & Henry, C. J. K. (2011). Does prolonged chewing reduce food intake? Fletcherism revisited. Appetite, 57(1), 295-298.

- Dhillon, J., Craig, B. A., Leidy, H. J., Amankwaah, A. F., Anguah, K. O. B., Jacobs, A., … & McCrory, M. A. (2016). The Effects of Increased Protein Intake on Fullness: A Meta-Analysis and Its Limitations. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 116(6), 968-983.

- Astrup, A., Belza, A., Ritz, C., Sørensen, M. Q., Holst, J. J., & Rehfeld, J. F. (2013). The contribution of gastroenteropancreatic appetite hormones to protein-induced satiety. The FASEB Journal, 27(1 Supplement), 249-4.

- Nair, K. S., Halliday, D., & Garrow, J. S. (1983). Thermic response to isoenergetic protein, carbohydrate or fat meals in lean and obese subjects.Clinical Science, 65(3), 307-312.

- Karst, H., Steiniger, J., Noack, R., & Steglich, H. D. (1984). Diet-induced thermogenesis in man: thermic effects of single proteins, carbohydrates and fats depending on their energy amount. Annals of nutrition and metabolism,28(4), 245-252.

- Dauncey, M. J., & Bingham, S. A. (1983). Dependence of 24 h energy expenditure in man on the composition of the nutrient intake. British journal of nutrition, 50(01), 1-13.

- Weigle, D. S., Breen, P. A., Matthys, C. C., Callahan, H. S., Meeuws, K. E., Burden, V. R., & Purnell, J. Q. (2005). A high-protein diet induces sustained reductions in appetite, ad libitum caloric intake, and body weight despite compensatory changes in diurnal plasma leptin and ghrelin concentrations. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 82(1), 41-48.

- Skov, A. R., Toubro, S., Rønn, B., Holm, L., & Astrup, A. (1999). Randomized trial on protein vs carbohydrate in ad libitum fat reduced diet for the treatment of obesity. International journal of obesity, 23(5), 528-536.

- Johnston, C. S., Tjonn, S. L., & Swan, P. D. (2004). High-protein, low-fat diets are effective for weight loss and favorably alter biomarkers in healthy adults. The Journal of nutrition, 134(3), 586-591.

- Clifton, P. M., Keogh, J. B., & Noakes, M. (2008). Long-term effects of a high-protein weight-loss diet. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 87(1), 23-29.

- Leidy, H. J., Hoertel, H. A., Douglas, S. M., Higgins, K. A., & Shafer, R. S. (2015). A high‐protein breakfast prevents body fat gain, through reductions in daily intake and hunger, in “Breakfast skipping” adolescents. Obesity, 23(9), 1761-1764.

- Hoertel, H. A., Will, M. J., & Leidy, H. J. (2014). A randomized crossover, pilot study examining the effects of a normal protein vs. high protein breakfast on food cravings and reward signals in overweight/obese “breakfast skipping”, late-adolescent girls. Nutrition journal, 13(1), 1.

- Bauer, L. B., Reynolds, L. J., Douglas, S. M., Kearney, M. L., Hoertel, H. A., Shafer, R. S., … & Leidy, H. J. (2015). A pilot study examining the effects of consuming a high-protein vs normal-protein breakfast on free-living glycemic control in overweight/obese ‘breakfast skipping’adolescents. International Journal of Obesity, 39(9), 1421-1424.

- Leidy, H. J., Ortinau, L. C., Douglas, S. M., & Hoertel, H. A. (2013). Beneficial effects of a higher-protein breakfast on the appetitive, hormonal, and neural signals controlling energy intake regulation in overweight/obese,“breakfast-skipping,” late-adolescent girls. The American journal of clinical nutrition,97(4), 677-688.

- Casa, D. J., Armstrong, L. E., Hillman, S. K., Montain, S. J., Reiff, R. V., Rich, B. S., … & Stone, J. A. (2000). National Athletic Trainers’ Association position statement: fluid replacement for athletes. Journal of athletic training, 35(2), 212.

- Cheuvront, S. N., & Kenefick, R. W. (2014). Dehydration: physiology, assessment, and performance effects. Comprehensive Physiology.

- Buehrer, S., Hanke, U., Klaghofer, R., Fruehauf, M., Weiss, M., & Schmitz, A. (2014). Hunger and thirst numeric rating scales are not valid estimates for gastric content volumes: a prospective investigation in healthy children.Pediatric Anesthesia, 24(3), 309-315.

- Yosten, G. L., & Samson, W. K. (2013). 6 Separating Thirst from Hunger.Neurobiology of Body Fluid Homeostasis: Transduction and Integration, 67.

- Brannigan, M., Stevenson, R. J., & Francis, H. (2015). Thirst interoception and its relationship to a Western-style diet. Physiology & behavior, 139, 423-429.

- Stookey, J. D. (2010). Drinking water and weight management. Nutrition Today, 45(6), S7-S12.

- Parretti, H. M., Aveyard, P., Blannin, A., Clifford, S. J., Coleman, S. J., Roalfe, A., & Daley, A. J. (2015). Efficacy of water preloading before main meals as a strategy for weight loss in primary care patients with obesity: RCT. Obesity,23(9), 1785-1791.

- Davy, B. M., Dennis, E. A., Dengo, A. L., Wilson, K. L., & Davy, K. P. (2008). Water consumption reduces energy intake at a breakfast meal in obese older adults. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 108(7), 1236-1239.

- Daniels, M. C., & Popkin, B. M. (2010). Impact of water intake on energy intake and weight status: a systematic review. Nutrition reviews, 68(9), 505-521.

- Dennis, E. A., Dengo, A. L., Comber, D. L., Flack, K. D., Savla, J., Davy, K. P., & Davy, B. M. (2010). Water consumption increases weight loss during a hypocaloric diet intervention in middle‐aged and older adults. Obesity, 18(2), 300-307.

- Phillips, R. J., & Powley, T. L. (1996). Gastric volume rather than nutrient content inhibits food intake. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 271(3), R766-R769.

- Powley, T. L., & Phillips, R. J. (2004). Gastric satiation is volumetric, intestinal satiation is nutritive. Physiology & behavior, 82(1), 69-74.

- Ello-Martin, J. A., Roe, L. S., Ledikwe, J. H., Beach, A. M., & Rolls, B. J. (2007). Dietary energy density in the treatment of obesity: a year-long trial comparing 2 weight-loss diets. The American journal of clinical nutrition,85(6), 1465-1477.

- Ledikwe, J. H., Rolls, B. J., Smiciklas-Wright, H., Mitchell, D. C., Ard, J. D., Champagne, C., … & Appel, L. J. (2007). Reductions in dietary energy density are associated with weight loss in overweight and obese participants in the PREMIER trial. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 85(5), 1212-1221.

- Rolls, B. J., Roe, L. S., Beach, A. M., & Kris‐Etherton, P. M. (2005). Provision of foods differing in energy density affects long‐term weight loss. Obesity Research, 13(6), 1052-1060.

- Ledikwe, J. H., Blanck, H. M., Khan, L. K., Serdula, M. K., Seymour, J. D., Tohill, B. C., & Rolls, B. J. (2006). Dietary energy density is associated with energy intake and weight status in US adults. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 83(6), 1362-1368.

- Clark, M. J., & Slavin, J. L. (2013). The effect of fiber on satiety and food intake: a systematic review. Journal of the American College of Nutrition,32(3), 200-211.

- Ye, Z., Arumugam, V., Haugabrooks, E., Williamson, P., & Hendrich, S. (2015). Soluble dietary fiber (Fibersol-2) decreased hunger and increased satiety hormones in humans when ingested with a meal. Nutrition Research,35(5), 393-400.

- Slavin, J. (2013). Fiber and prebiotics: mechanisms and health benefits.Nutrients, 5(4), 1417-1435.

- Beccuti, G., & Pannain, S. (2011). Sleep and obesity. Current opinion in clinical nutrition and metabolic care, 14(4), 402.

- Murphy, K. (2011). Sleep and obesity. Australian Journal of Medical Herbalism, 23(4), 190-191.

- Patel, S. R., Blackwell, T., Redline, S., Ancoli-Israel, S., Cauley, J. A., Hillier, T. A., … & Yaffe, K. (2008). The association between sleep duration and obesity in older adults. International journal of obesity, 32(12), 1825-1834.

- Qureshi, A. I., Giles, W. H., Croft, J. B., & Bliwise, D. L. (1997). Habitual sleep patterns and risk for stroke and coronary heart disease A 10‐year follow‐up from NHANES I. Neurology, 48(4), 904-910.

- Bopparaju, S., & Surani, S. (2010). Sleep and diabetes. International journal of endocrinology, 2010.

- Cappuccio, F. P., Taggart, F. M., Kandala, N., Currie, A., Peile, E., Stranges, S., & Miller, M. A. (2008). Meta-analysis of short sleep duration and obesity in children and adults. SLEEP-NEW YORK THEN WESTCHESTER-, 31(5), 619.

- Landis, A. M., Parker, K. P., & Dunbar, S. B. (2009). Sleep, hunger, satiety, food cravings, and caloric intake in adolescents. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 41(2), 115-123.

- Taheri, S., Lin, L., Austin, D., Young, T., & Mignot, E. (2004). Short sleep duration is associated with reduced leptin, elevated ghrelin, and increased body mass index. PLoS Med, 1(3), e62.

- Chaput, J. P., Després, J. P., Bouchard, C., & Tremblay, A. (2007). Short sleep duration is associated with reduced leptin levels and increased adiposity: results from the Quebec family study. Obesity, 15(1), 253-261.

- Nedeltcheva, A. V., Kilkus, J. M., Imperial, J., Kasza, K., Schoeller, D. A., & Penev, P. D. (2009). Sleep curtailment is accompanied by increased intake of calories from snacks. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 89(1), 126-133.

- St-Onge, M. P., Roberts, A. L., Chen, J., Kelleman, M., O’Keeffe, M., RoyChoudhury, A., & Jones, P. J. (2011). Short sleep duration increases energy intakes but does not change energy expenditure in normal-weight individuals. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 94(2), 410-416.

- Björntorp, P. (2001). Do stress reactions cause abdominal obesity and comorbidities?. Obesity reviews, 2(2), 73-86.

- Epel, E., Lapidus, R., McEwen, B., & Brownell, K. (2001). Stress may add bite to appetite in women: a laboratory study of stress-induced cortisol and eating behavior. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 26(1), 37-49.

- Rosmond, R., Dallman, M. F., & Björntorp, P. (1998). Stress-related cortisol secretion in men: Relationships with abdominal obesity and endocrine, metabolic and hemodynamic abnormalities 1. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 83(6), 1853-1859.

- {{cta(‘a7bb1718-22d3-4987-80f1-5e01154e492d’,’justifycenter’)}}